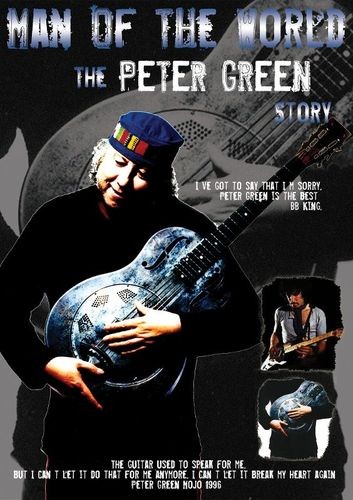

DVD – DOCUMENTARY

Man of the World: The Peter Green Story

About halfway through Man of the World: The Peter Green Story, Noel Gallagher tells the story about hearing “Man of the World” on the radio and running out to buy a bunch of Fleetwood Mac albums to play for the band. When he did, no one recognized the music. “Who are they? This isn’t Fleetwood Mac,” someone said. No one believed it was Fleetwood Mac. “Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac,” Gallagher explained. That kind of thing surely happens frequently when people don’t know this was a completely different band than the one you hear all over classic rock radio. It’s like the scene in High Infidelity when John Cusack’s character plays the Beta Band on the record store record store system, knowing he’ll sell a few copies immediately. All you have to do is listen, and you know there are a lot of great tunes there. And you get to hear a lot of them as the backdrop to a fascinating story.

Peter Green formed Fleetwood Mac in 1967 after playing in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers (in which he replaced Eric Clapton) with John McVie and Mick Fleetwood. Mayall had given him studio time for his birthday to record something as a trio, and it stuck. He lured Fleetwood and recruited guitarist Jeremy Spencer and bassist Bob Brunning, who stayed until Green could finally convince McVie it would be safe leaving the Bluesbreakers to join him. He didn’t even want to name the band after himself. One of the more heartwarming revelations is Green’s motivation, something McVie claims he never knew until years later. Spencer says Green told him at some point, he knew he’d leave the band, and that Spencer would leave the band, and Green wanted Mick and John to be able to keep building on the name without them.

The film is a fairly straightforward chronological exploration of Green’s musical life, weighted heavily toward the Fleetwood Mac years, which is most of the two-hour film. Green himself was interviewed extensively, as were Fleetwood and McVie, manager Clifford Adams, and contemporary Carlos Santana. The story is told with compassion and a fair bit of humor.

The die-hard may be well familiar with this, but I never knew Fleetwood Mac had, at least for a short while, acquired a reputation for being quite nasty onstage. Spencer remembers playing gigs with a condom full of milk hanging off of his guitar. Mick Fleetwood remembers the band finding a dildo in a red light district in Germany of Holland somewhere that they named “Harold.” “Harold,” says John McVie, contemplatively, in one of the more silly moments in the doc, “he appeared quite regularly. He was a standup guy.”

None of that is included to be shocking. Rather, it shows musicians who had locked themselves into a stylistic tradition beginning to open up and free themselves. “It was like an antidote to getting just too damn serious,” says Fleetwood. He found a pair of balls on a string in a bathroom at one gig, and now he says he never plays a Fleetwood Mac gig without wearing a pair on his belt. The next phase was acid, something they were convinced to do by the Grateful Dead’s soundman, Owsley. McVie is wonderfully constant and deadpan throughout his interviews. While Fleetwood talks about everyone freaking out on their first trip, McVie is much more understated. “I didn’t talk to god,” he says. “I just felt a bit strange.”

That freedom led to the breakthrough with Danny Kirwan, Then Play On, when they got away from the Elmore James-inspired blues Spencer favored. The musical awakening led to a spiritual awakening, something Green has clear memories about in the more current interviews. He wanted to give a portion of the band’s profits to charity. Great idea. Except the others weren’t quite as sure about giving away quite so much. “Oh Well” fit into that new philosophy, and Green takes great joy in recalling it. “It’s always nice to revisit yourself,” he says, smiling.

The movie builds to Green’s dramatic departure, from the band and reality. That arc started with at a party in Germany put on by what the rest of the band seems to agree was a cult, where drugs were flowing freely. The band’s then-manager Clifford Adams says after that, Green and Kirwan were mentally ill. And shortly thereafter, on the European tour, Green quit the band.

There’s an interesting diversion in the story here. On one side, you have the band members and management shocked Green is leaving and chalking it up to the party and the cult in Germany. On the other, you have Green saying he just wasn’t getting a jolt out of it anymore, and he needed to move on. Spencer made his own dramatic break after, as he said, hearing the voice of god telling him to go. In what seems like something out of a movie script, Green came back to help the Spencer-less band fulfill contract obligations. He never sang or played lead guitar until the final night of the tour at the Fillmore East, where he finally stepped up to the mic to play what Adams describes as a four-hour version of “Black Magic Woman.”

The, silence. For about ten years. The documentary doesn’t spend too much time on this period – just the last twenty minutes or so. Green wound up in a mental institution and was diagnosed schizophrenic. According to Adams, the drugs were just magnifying the problem. Green disagrees. “I didn’t think I was schizophrenic,” he says. “To them it’s schizophrenia,” he says. “To you, it’s hellishly single-minded.” There were problems with medication. He did return to making music, and the film could have spent a bit more time there, showing his return in some way. There’s a how and why missing toward the end. But if you’re looking to learn about Green and Fleetwood Mac, this is an excellent primer. This, and Noel Gallagher’s plan – go grab the albums and get familiar.