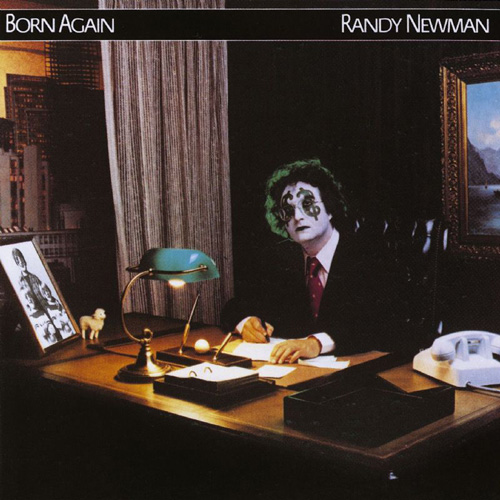

It was thirty-seven years ago this August that Randy Newman released his sixth studio album, Born Again. It’s an underrated album, as are most of Newman’s studio albums in terms of mainstream recognition. It’s full of wry and sarcastic tunes throwing haymakers at the facile, the ignorant, and the depraved. He addresses attitudes toward masculinity (“Half A Man”), upper class success (“Mr. Sheep”), and greed (“It’s Money That I Love”). He tells peculiar tales of an ELO-like band (“The Story of a Rock and Roll Band”) and perfect marriage gone wrong (“They Just Got Married”), the latter with a startling and cruel punchline. It was his sense of humor as much as anything that doomed Newman on Born Again, which fizzled on the charts. Jeff Giles explored that in a ” target=”_blank”>fantastic article for Ultimate Classic Rock last year.

There is one song in particular that stood out to me – “Pretty Boy.” I only found the album a couple of years ago after having listened obsessively to Sail Away for several years. I’ve always enjoyed Newman’s sense of humor and his ability to tell a vivid short story in three or four minutes. The first time I heard “Pretty Boy,” I must have hit repeat dozen times. It’s a thrilling and unsettling piece of songwriting.

There is more menace in “Pretty Boy” than in ninety percent of the songs I hear across however many genres packed with volume and swagger, engineered to intimidate philosophically or sonically.

Newman’s lyrics are fantastic, but I would urge you not to read them before you listen. It’ll lose a bit of its impact. In fact, listen to it now before you read this rest of what I have to say about it. I don’t want to ruin it for you. Find a place where you can pay attention to the words.

“Pretty Boy” is understated, musically. Newman doesn’t shout. You don’t see the knife, but you know it’s there, and you know it’s about to be revealed. It’s a trick directors use frequently, implying the violence and letting your imagination fill in whatever frightens you most. Everything happens off-screen. Think of the “Ear Scene” in Reservoir Dogs, when the camera pulls away to the shot of the warehouse door, and Michael Madsen steps outside into the silence and casually retrieves a gas can from the trunk of his car, and how much scarier that is than what happens once he’s back inside. That’s the moment this song captures. Masterfully. It’s a four-minute Scorsese film.

At the time, that approach was seen as a drawback to some critics. Stephen Holden didn’t pan the album outright in Rolling Stone, but he wasn’t glowing in his interpretation, either, especially concerning “Pretty Boy.” “Born Again’s dramatic setups ring as false as its moralism,” he wrote. “The almost impenetrable ‘Pretty Boy’ suggests an incipient street fight, but the song ends before the action starts.” I find it satisfying, though, that Holden reviews Born Again in tandem with the soundtrack for Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeny Todd.

What’s strange to me about that is how vivid the song was for me the first time I heard it, and how the view expanded the more I listened. “Have we got a tough guy here?” Newman sings over spare, droning piano. “Have we got a tough guy from the streets? Looks just like that dancing wop in those movies that we seen.” No way to misinterpret this character’s intentions. He is contemptuous and violent. Whatever follows those words, blood will be involved.

With the cute little chicken chit boots on, his cute little chicken shit hat.

His cute little chicken shit girlfriend riding along in back

Now we’ve got a complete image. A wannabe tough guy behind the wheel of his car has the bad luck to run into some actual tough guys. Newman doesn’t mention that the wannabe has a friend riding shotgun. But for some reason, the girlfriend is riding in the back. What that tells me is that the wannabe knew they were about to drive through a neighborhood and didn’t want his girlfriend to be seen. That’s failed now. The toughs have seen her, and if they could have escaped, there wouldn’t have been a second verse. Now they’re trapped. Now they have to wait for whatever’s coming.

What’s been happening with you boys?

Are you having a nice time on your trip?

All the way from Jersey City, you look pretty as a picture

Please don’t hurt no one tonight

Please don’t break no woman’s heart

How ’bout it, you little prick?

How ’bout it?

“Boys” makes me wonder if there’s another wannabe in the car, but tough guy never uses a plural again. But he has size up Pretty Boy perfectly. Knows his type, knows where he’s from, knows his bravado, which is being severely tested, if it hasn’t evaporated already. And there’s a shift in attitude in the last part of the verse, from mocking to outright hostility, which leads to the bridge. Newman plods heavily on the piano as cello’s take up the dramatic them. A high-pitched tone like an emergency broadcast test, or like an oncoming aneurism, swells in the background until it’s popped with blasts of synth. When the volume settles back down, Newman’s voice is calm again.

Hope we’re gonna get the chance to show you ’round

Hope we’re gonna get the chance to show you ’round

Talk tough to me, Pretty Boy

Tell us all about the mean streets of home

Talk tough to me

The tough guy is done talking, and that’s where the song ends. As terrifying as his talking might have been, it’s when he stops that the real terror starts. And just like in Reservoir Dogs, you get to use your imagination to fill in the rest. And Newman has led you to a point where you can only imagine the worst, and that scene, the one he didn’t write, will be the most frightening, because it will be personal. It will be the listener’s creation, whatever they find the most terrifying. Most probably, that’s not going to end with the tough guy putting Pretty Boy in a headlock, giving him a loving noogie, and saying, “Just kidding! Whoooeee! You should’ve seen your face, man. Here’s a greeting card with some glitter in it. We all signed it. My regards to Jersey!”

Nope. Talking is done. Time for action. Time for blood.