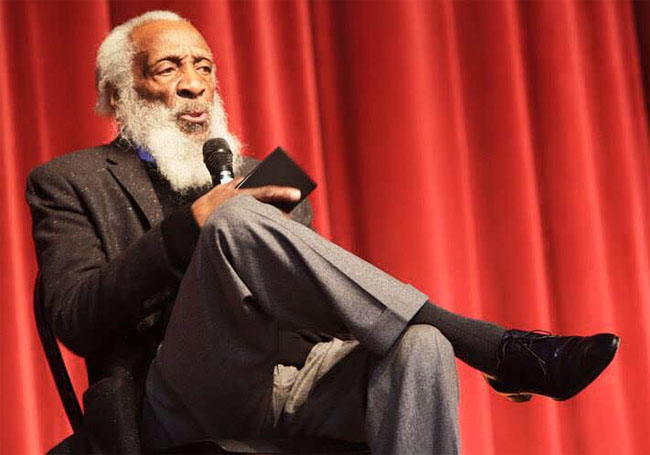

The world lost a tremendous voice for comedy and civil rights activism Saturday night when Dick Gregory died at 84, reportedly of a bacteria infection. I was privileged to have spoken with him twice over the years for the Boston Globe and the long defunct Gadfly Magazine. I interviewed him for the first time in 2002, around the same time I had interviewed Mort Sahl. Both of them had been personal witnesses to so much history, and it didn’t take much to get it out of them. You could mention a couple of names and dates and sit back and let them school you. They were both being honored at HBO’s Aspen U.S. Comedy Arts Festival, and I spoke with Gregory just before the Festival was to happen.

I’ve included the longer transcript of the interview hear, the one that Gadfly Magazine published. I also interviewed Gregory in 2010 before a rare stand-up show at the Wilbur in Boston. It was the only time I got to see Gregory in person. At that point, he had long since quit the club scene to concentrate on activism, which is why, when we spoke about whether he thought his comedy was an extension of that activism, I was so surprised by his answer. He didn’t think anything he or any other comedian did onstage would change all that much.

“Oh, no no,” he said. “Look, look. When I go up onto that stage, I don’t go up there to heal nobody. I go up there to be funny. If I healed everybody’s problems and I didn’t get one laugh, I’d walk out of there defeated and I’d probably give them folks their check back. When I’m out there demonstrating for women’s rights and human rights and everybody laughs, I’m defeated. We will find a cure for cancer. We will find a cure for all that ails us and it won’t be through no comics, it won’t be through no entertainers, it won’t be through no athletes. Some little people who we ain’t never heard of, the girl you probably wouldn’t even go to the high school prom with. A little nerd, right? That’s where this is going to be found.”

I’ll release more of that interview eventually, but I wanted to go back to the original interview from 2002, when we spoke about modern comedy, civil rights history, the difference between humor and comedy, and a whole lot more. Or, I should say, Gregory spoke, and I listened.

From Gadfly Magazine, 2002:

In the early 1950s, there was a revolution brewing in the comedy clubs. Lenny Bruce, as guilty as anyone of hamming it up with cheap impressions and forgettable punchlines in his early years, was starting to become a different monster when the cameras were off. Mort Sahl was dissecting politics and talking directly to the audience about substantive issues. And Dick Gregory was confronting racial and social issues no one had dared mention onstage in front of racially mixed audiences.

Gregory was recently honored at the Aspen U.S. Comedy Arts Festival in its tribute to free speech, helping to bring him a bit more into focus for his contributions to the art of stand-up comedy. Gregory, along with Sahl, tends to get overshadowed by the legacy of Lenny Bruce when it comes to a discussion of comedy pioneers. One look at the list of people he knew and worked with, though, shows his reach and place in not only comedic history but in Civil Rights history as well. Martin Luther King, Jr., James Meredith, Malcolm X, Jack and Bobby Kennedy–Gregory is connected to each name.

He formed protests in his native St. Louis when he was just a boy, marched in Mississippi and spoke to crowds in Washington in 1963, was shot in the riots in Watts in 1965 and took on Mayor Richard J. Daley, Jr. in the 1966 Chicago elections. In 1973, he stopped performing in clubs to dedicate more time to the Civil Rights movement. He maintains a schedule of speaking dates, provides material for his Web site, recently updated his memoirs with Callus on My Soul from Longstreet Press, and released a three CD recording of his 21st Century State of the Union.

Gadfly interviewed him by phone before the Aspen Comedy Festival.

Gadfly: What does it mean to you to be honored at Aspen?

Dick Gregory: Well, it means… There’s different types of honors. You can get an honor from, let’s say the Newspaper Guild, or an honor from your college, but to get an honor from your peers–those ones you can’t trick. These are comics. And people who have spent the biggest part of their life in comedy and performing. Then you have the joining with the free speech movement and First Amendment rights. These are folks, you’re not just getting an award because you are a celebrity or they are awed by you. You’re getting it because these are folks that have been able to dissect your career. It’s been on the front, looking and listening, so it means a whole lot to me from the standpoint as a comedian.

I stood flat-footed when I started in show business, and I would do a routine about the Mafia and how much grip they have on Chicago and the political machine. And I had cops who’d come by the club and say, “Man, you better be careful, they’ll blow this whole place up.” If that’s the price you have to pay, let’s pay it. That’s easy, to stand in a nightclub, where most of the people that come in, they came to see you. It is mean to go to Mississippi marching, where the people who could kill you didn’t invite you. It was two different trends. It’s one, being on the stage tonight for people who basically love you, who’s paying to see you. And the next day you marching in a line.

To be in Birmingham when the firemen turned the hoses on us. And to get outraged, but before your outrage can get formed in your brain, you see something pass by you really swiftly from the force of that water, and it’s a little four-year-old, five-year-old child. Before your anger can come up, you see a white nun that sweeps past you, then a priest or an old black minister or an old black woman, and the line keeps moving. It’s almost like, you trying to get an attitude and you gettin’ in the way. Because you’re fixing to do something to the line that the cops and the hoses couldn’t do. I’m fixing to slow up their progress, cause I’m thinking, “My God, they treated all of us…” Then you realize, there’s something in this line more beautiful than me, and more beautiful than what they’re doing to let me decide which one of these I want to join. And I fall back into the line. And fell back into the motion where the people was. It was just a wonderful feeling, sitting there at night realizing there’s something that happened that I couldn’t explain. I could not explain just ordinary people.

Is that part of what led you away from the nightclubs in 1973?

I got out of the nightclubs because my loyalty was to the movement. And I just felt that I was doing you a disservice as a nightclub owner, that would bring me in at top dollar and then advertise for six months, and intense advertising the last three weeks, and then something come up in Mississippi or Alabama or Chicago, and I would go to it. So I just thought that I was being unfair to the nightclub owners. There were some nightclubs that probably wouldn’t bring me in at all, but I wasn’t worried about them. I was worried about the ones that did.

And then the other thing is I sat and realized one day, do I really want to take this talent that I got, and use it to expose young folks to alcohol. At that time, we didn’t know that cigarettes, secondary smoke, was bad. I didn’t know that. And I made that decision at a time when I was smoking four packs of cigarettes a day, and I’d been drinking a fifth of scotch a day. So I wasn’t making decisions based on what was right, or healthy or nothing like that. I was making it based on, I just felt bad, in a nightclub where they say it’s like x amount you pay to get in, and then a two or three drink minimum–people just seemed stupid to come in and get a Coke when you could get a rum and Coke and pay the same thing. Get a rum, they’ll give you the Coke.

Did you quit performing altogether?

No. Back then, when you got out of nightclubs, that was about 95 percent of where you would work. My act was more of a cabaret act than it was a concert act. I would do concerts. But basically my whole thing was to relate to the audience. It was the difference in doing a play and a movie. And after I got out of that, you know, whenever I go and speak now, I do about 200 lecture dates a year. It’s a different type of funny. I mean, I’m funny as hell. But nothing takes the place of walking out on that, you know, when I come to do a lecture, I don’t need the timing and the sharpness to do a joke. But when you are just standing out on that stage, just raw naked, you and that audience.

I know in your 21st Century State of the Union, when you’re talking about a more serious subject, sometimes a routine will come out about coffee, or a bit on what Stevie Wonder’s wearing. Does that satisfy your comedic impulses?

No, that’s more humor. When you and your friend sit around and you all laughing and talking, that’s humor. Comedy is a professional person that stands up and says, “Da da da da da da …” That’s altogether different. I enjoy it because all my life I’ve been like that. There’s no way I would talk all this time if I wasn’t saying something funny. That’s altogether different than walking on the stage, because when you’re walking on the stage, your breath, your move, everything is perfect. It’s all coordinated. It’s the difference between a boxer and someone fighting.

When you first started doing the more political material, how did you feel the audiences were reacting to that?

Oh, they were reacting not as much to me. But remember, I’m seventy years old and it was the infancy of television. And, you know, there was a time something could happen in Afghanistan, and it would be two years before you could physically see it. If a plane crashed in India or Russia today, those bodies is in your living room tonight. Well, back then the news wasn’t moving that fast, but it was fast enough where I could walk up on the stage and just a bare minimum, kind of give you a brief background.

Whereas before, for instance, when I first started out, about ninety-nine point nine percent of black folks had never been on an airplane in they life. So when Shelly Berman came out with a best-selling comedy album called “Coffee, Milk, or Tea”, mocking the stewardess… Well, I could never do that in a black neighborhood because they’d never been on a plane. But I could develop the same type of routine, but dealing with a Greyhound Bus.

Now, you could go anywhere and do any type of routine because people who live in Gooseneck, Tennessee is exposed to the Metropolitan Opera. All you got to do is just turn on cable. People who don’t have the money to go to a movie can turn on cable. So you can go now and take the number one movie in America, and you could do five minutes of comedy on it and you wouldn’t lose too many people. Although most of the audience sitting at home haven’t seen it, but they know about it.

When I was in the military, I’d walk onstage and say, “I was arrested this morning for impersonating an officer. I slept until twelve noon.” Well, the military can wreck you as a comic because you can tell some of the squarest jokes and get the best audience in the world because they don’t have nothing else to do.

I was going to ask you about the Army talent show in 1954. You had said in your book that your act back then was too political.

I have no doubt. The guys who won it, they even told me they felt sorry. I realize now that was a blessing from God because the winner got to go on the Ed Sullivan Show. And had I gone on the Ed Sullivan Show, as big as Ed Sullivan was at the time–that was the show–I would have failed as a comic because I was not a good comic. I didn’t know timing. And it would have been hard for someone to tell me that I wasn’t the hottest thing in the world. So I realize now that my blessing from God was, I didn’t make it on the Ed Sullivan Show.

It seems like, today, a lot of people are shooting for that “Ed Sullivan shot,” and that’s probably what ruins a lot of great comics.

Yeah, you’re right. First, let’s go back. First, you have comics… What ruined a lot of good comics was Richard Pryor. Richard Pryor is a genius. Redd Foxx probably had the most profanity and risqué material of any comic in the history of show business at that time. And when you were sitting around and they brought out a Redd Foxx record, you knew all the Christians was gone. You knew anybody that felt anything about spirituality was gone.

And then Richard Pryor came through, and we were so into his genius that we didn’t hear the profanity. So we played those records in the family room with the children because we absolutely did not hear the profanity, we heard his genius. Well, to a five-year-old child, there is no genius. That five-year-old child heard the profanity. So when they came through, they wanted to pattern themselves after Richard Pryor cause there was one string in there after another. But the one thing they failed to realize, and rightfully so, if you go take all of Richard Pryor’s tapes, all his comedy, all his raw, naked comedy and take the profanity out, it’s just as funny because he never had to use profanity as a punchline. They didn’t hear that. And then you turn on Def Jam, and you don’t see nobody on there that ain’t talking about something gross and filthy–and I have no problem with that. I have no problem with that at all, but not for television. And then they develop, and once you develop that kind of comedy routine, you can’t grow because you have to top it.

I wanted to talk a bit about black comedy, and if that term is even…

Oh, yeah. Sure. Black comedy. Two terms–black comedy and black humor. Black humor has been there for years. Black comedy was a victim of racism.

I didn’t realize, when I decided to be a comic, that a black person had never been allowed to stand flat-footed in America and talk to white folks. It never happened before. You could sing, you could dance, you could stop and tell a joke while you were dancing, but you could not just stand flat-footed. That was not permitted. When Hugh Hefner brought me in, that was the first time that had ever happened in the history of America. And when I went on the Jack Paar Show, which was the old Tonight Show, I was the first black that was permitted to sit down on the couch and talk. I didn’t realize that when you came and did your act, nothing happened. But when you sit down, you become part of the family. My salary jumped from $250 a week to $5,000 a night. That was the importance of that Tonight Show. It was just incredible. I was getting letters from white folks for years–”I didn’t know Negro children and white children were the same…” They never had heard a black person. That’s hard to believe today. They’d never heard a black person sit down and talk about they family. They’d seen black folks entertain, they’d seen them play sports, but they’d never heard them talk.

When you working, you very seldom get to see other people that’s working. Especially if other people is good, because people who’s good don’t work late. So I had heard of… Doctor Dolittle?

Eddie Murphy?

Eddie Murphy. I had heard of Eddie Murphy. I’d seen little snaps of him, but I went to see him down on Martha’s Vineyard. And there ain’t no black people in the audience because white folks go and get their tickets three months in advance, but I was on payday. So there it was like three black folks in the audience. And Eddie Murphy walks out and says, “I know a bunch of you ignorant, redneck, cracker motherfuckers are going to get mad at some of the shit I’m going to say so I’m just going to tell you now–Get up, suck my dick, and get the fuck out of here.” And those folks cheered! Cheered! I said, “Oh, my God, what have I missed?” So I literally got on the phone and called my wife and said, “Have one of your children put you in a car and drive you down here, because I want to show you where this thing has gone to.” And honest to goodness, if any white person got up to leave, those folks probably would have jumped on him. That’s how far this thing has gone. That’s how far from the day when I was out there.

Have you gotten to see Chris Rock or the Kings of Comedy?

Oh, yes. Fabulous. Just fabulous. It’s not just comedy, it’s a whole new attitude. I couldn’t have had that attitude when I was coming out because the whole American Society just accepted a black person getting on the stage. I had my routine down.

Do you think free speech is better today than it was, say, thirty years ago or fifty years ago?

Oh, yeah. There was a time when a woman did not ever walk up onstage and say, “All of you motherfuckers shut up, I’ve got something to say to you,” and then go and do her act. Oh, my God, please. Jesus Christ. I mean, it hasn’t totally opened up for women. In other words, you and I could go to a football game, you could pull your clothes off and run all the way across that stadium, they’d call it streaking. You let a woman do it, and it would not be called streaking. She’d be called a whore… Who is she? Put her out of here. Is she a student? Get her out…

Get her phone number first, but get her out…

[laughs] Yeah. No, I think where the level of free speech is today, it’s incredible. My God. There is no comparison. I mean, absolutely none whatsoever, compared to what women were locked into, what black folks were locked into, what Asians were locked into.

Do you think free speech is in any danger post-September 11th?

Oh, God, yes. I mean, we don’t know the magnitude of it yet. But I don’t think it’s the type of free speech from talking about what’s happened. I think of the new laws that’s coming through. I mean, just free speech or free movement.