MUSIC

1. Drive-By Truckers – American Band

The Drive-By Truckers may be the definitive American band. Others may have a rootsy sound, or play inspired rock and roll. Some may speak to the politics of the times. But no one puts it together like the Truckers, and that’s especially true on the new album, American Band, their most explicitly and consistently political since Southern Rock Opera. Singer/guitarist/songwriter Patterson Hood promised as much in June when the band released the Mike Cooley-penned “Surrender Under Protest,” Cooley’s reaction to the Confederate flag being taken down over the South Carolina State House after nine people were gunned down in a black church in the summer of 2015. “Compelled but not defeated, surrender under protest if you must,” sang Cooley, speaking to those who would keep the flag flying out of a sense of tradition. Hood wrote on the band’s Web site that though the band has never been shy to write about politics, it has mostly addressed historic issues or wrapped it in the artifice of a story. “This time out,” he wrote, “there are no such diversions as these songs are mostly set front and center in the current political arena with songs dealing with our racial and cultural divisions, gun violence, mass shootings and political assholery.”

This album might be dealing in the present, but Cooley and Patterson are still writing compelling fables with flawed characters. They come out swinging, sonically and lyrically, on Cooley’s “Ramon Casiano,” the story of a crooked border agent involved in a killing as a boy. It’s some of Cooley’s best songwriting, and typical of the more pointed lyrics on the album.

He had the makings of a leader

Of a certain kind of men

Who feel the world’s against them

Out to get them if it cam

Men whose fingers pull their triggers

Men who would rather fight than win

United in a revolution

Like in mind and like in skin

Hood’s contributions often find him longing for a time or place beyond the turmoil of modern violence. In “Guns of Umpqua,” he addresses the shootings that killed a professor and eight students at a community college in Oregon in 2015. His narrator is trying to escape the memory of witnesses the shootings, which he recounts in some detail. “We’re all standing in the shadows of our noblest intentions of something more/Than being shot in a classroom in Oregon,” sings Hood. The song ends on the refrain, “Heaven’s calling my name from the hallway outside the door.” Hood’s at his most ferociously political on “What It Means,” addressing killing and rioting in Ferguson, Missouri and the Trayvon Martin case in Florida. “I mean Barack Obama won and you can choose where to eat,” he sings, “but you don’t see too many white kids lying bleeding on the street.”

Musically, the band has settled into their sound with this line-up, their second album with a two-guitar attack with Cooley and Hood, Jay Gonzales on keys and sometimes guitar, and Matt Patton and Brad Morgan laying down bass and drums. It’s a muscular variation of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers on the more rock and roll tunes, which is sort of a base configuration they can dip in and out of for ballads like “Once They Banned Imagine” or the slinky boogie of “Kinky Hypocrite.”

Not every song on American Band is identifiable as headline news, but they all speak to the times. There’s the melancholy of Hood’s “Sun Don’t Shine,” about being happy when it gets cold outside and there’s “a little rain to make the roses bloom.” Even that mentions a love that will last “till the markets crash and smoke and ash is left of these beautiful trees.” That’s echoed in Cooley’s “Filthy and Fried” when he sings, “Everyone claims that the times are a changing as theirs pass them by/And everyone’s right.” The closing tune isn’t explicitly about Prince dying, but it’s not hard to imagine. “Some asswipe on TV said that you should be ashamed/For your cowardice in facing down your flaws/I’m not sure what makes me sadder, all that talent up in flames/Or the lack of understanding that it wrought.” And if there’s a theme that ties it all together, it’s more emotional than political. “All this freight can put you six feet in the ground/Nothing left to do but try to keep it all together/Better off without the baggage I carry around.”

2. Bob Weir – Blue Mountain

2. Bob Weir – Blue Mountain

I wasn’t entirely sure what to expect from a Bob Weir solo album, his first since 2004. Apparently, going into production of Blue Mountain, neither as Weir. “The project itself, as it unfolded, we hit – in the writing, in the composition of the music and lyrics – a stride that was kind of unexpected for me,” he says in the press release. The first thing I felt was the warm, enveloping sound of it. It speaks to wide-open spaces and lonely contemplation, and it reminded me more than a little bit of Neil Young’s Harvest Moon. That’s before I read about the concept and making of it. This is a collection of cowboy songs, a fascination of Weir’s since his younger days visiting and working in Montana, co-written with songwriter Josh Ritter. Don’t expect any songs about legendary gunfights or outlaws – Weir isn’t looking to further myths of the American West. He’s thinking more of the everyday reality of the times. This is where Weir and Ritter prove an effective songwriting team. The sound of the music perfectly reflects the stories of people inseparable from the land that supported them. The narrator in “One More River to Cross” starts his story with a list of the rivers he’s seen, singing, “I’m tired, but I still got one left in me yet.” On the waltzing “Whatever Happened to Rose,” the narrator is looking for his lost love in honkytonks and church yards, in case he finds her name on a stone to say one last goodbye. There are some more traditional touches. “Ki-Yi Bossie,” with its singalong chorus, sounds like something could have been featured in a Gene Autry film, save for its references to 12-step programs and saving whales. “Ghost Town” has the requisite guitar twang, and its bluesy runs are a rare nod to Weir’s playing with the Grateful Dead. Weir is right about this album being an unexpected stride in a different direction. But where he wound up, he seems right at home.

3. Luke Winslow-King – I’m Glad Trouble Don’t Last Always

3. Luke Winslow-King – I’m Glad Trouble Don’t Last Always

Luke Winslow-King doesn’t stick closely to one style on I’m Glad Trouble Don’t Last Always, his fifth studio. He opens with the gentle gospel “On My Way,” takes a leap over to “Voodoo Chile” inspired blues on the title track, makes another jump over to the laidback pop of “Change Your Mind,” then country folk of “Heartsick Blues.” There’s a nice Tom Waits-style rumble to the rhythm section to the bluesy “Esther Please,” and a nice pop to his boogie on “Act Like You Love Me.” The one thing that’s consistent throughout is a smooth delivery, in Winslow-King’s vocals and from his backing band. It’s somewhere in a league with Bob Schneider and Lyle Lovett. Some tasty stuff.

4. The Wytches – All Your Happy Life

4. The Wytches – All Your Happy Life

This album throbs with the heaviness of an imploding star. The Wytches come on like King Crimson on “C Side,” the first tune on All Your Happy Life, dissonant guitars causing a mental friction that makes them impossible to ignore. And that’s just the intro. Then come the angular riffs, the hip-swaying verses, and the old-school organ supporting the chorus like the ghost of Richard Wright circa 1968. There are heavy doses of loud psychedelic and surf rock mixed with metal. An old bio labeled Kristian Bell’s vocal delivery “feral,” and it’s hard to improve on that description. This trio plays full-throttle, whether it’s the monster-movie theme “Ghost House” or the slow menace of “Dumb-Fill,” they are laying into it. Their sense of dynamics doesn’t count on loud/quiet as much as it does melody versus upheaval. On “Throned,” that transition only takes a few seconds to develop. A melody is introduced, and then dashed by a thistle of guitar noise. As raucous as Wytches get, they never sound unhinged. They play with abandon and precision. That ain’t easy, and neither is the music. It’s unsettling in a wonderful way.

COMEDY

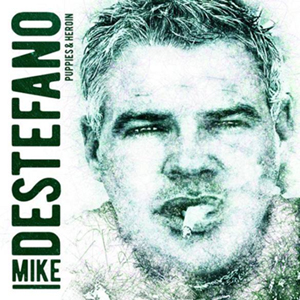

1.Mike DeStafano – Puppies and Heroin

1.Mike DeStafano – Puppies and Heroin

Ever have a friend whose heart is in the right place, but his mouth is rarely in that same zip code? That was Mike DeStefano. The Bronx-born comic got his biggest break on Last Comic Standing in 2010 and was just getting his career going when he died of a heart attack at 44 in 2011. This material on this album comes from two performances at a club in Minneapolis shortly before his death. His persona was a bit rougher than he was able to portray on network TV. And he’s lovingly antagonistic with this crowd from the start. He doesn’t trust them. They’re too nice. “I’m a nice person,” he says, “but it’s real easy to get me to be a prick.” He knows when he’s being a prick, and he celebrates it. “If I was in charge of karma, shit would be bad,” he says. “I’d be like, ‘Oh, you wanna go out to dinner? No?! Face cancer!’ You know what I’m saying? I’d overdo it. I’m sure I’d be bad at it.” He’s got some hilarious spins on prejudice, calling out people for being merely tolerant of gay people, as if it were their place to judge someone else to begin with. He hates the idea of anyone being in the closet – who’s so important that they’d have to hide who they are from anyone? As a former addict, DeStefano used to counsel fellow addicts, He remembers one guy who told him he’d had sex with a man for drugs. “He’s like, ‘Do you think I’m gay?’ And I said, ‘I think you’re worrying about the wrong fucking thing.’” But then he says some dumb things, that men are born gay but women aren’t, they just turn gay when they hate men. It goes back to that friend, who if they said that at a party, you’d be compelled to say to the horrified guests, “He doesn’t really mean that, he’s really a good guy.” And likely DeStefano would double down. The most compelling part of DeStefano’s comedy is the push and pull between the life-affirming story of his beating addiction and his anti-hero attitude about it. At one point, he tells the crowd, “Guys, I’ve had an amazing life. I was a fucking heroin addict, and I’m here.” Then he chides them for applauding. The lady in the audience who’s never done heroin probably deserves more applause. And she should be the one talking to kids about not doing heroin. “You’re better at it than me,” he says. What you get here is full, flawed humanity, celebrated for what it is, with no apologies necessary.