By the time Levon Helm’s music really struck me, he had already lived several lifetimes. He’d had his wild days on the road as a youngster drumming and singing in clubs across Canada and the US with Ronnie Hawkins. He’d played with Dylan and then quit the band to work on an oil rig in Houston when they got booed, and come back so The Band could exist and make several landmark albums. He’d already gone through an acrimonious split with Robbie Robertson, reformed The Band. Throat cancer had left him with bills to pay and no voice to sing for his supper, and his house in Woodstock had burned down. When I found him, or rather, when I realized exactly what I’d been missing for years, Helm had risen from a world of troubles to make some of the best music of his career.

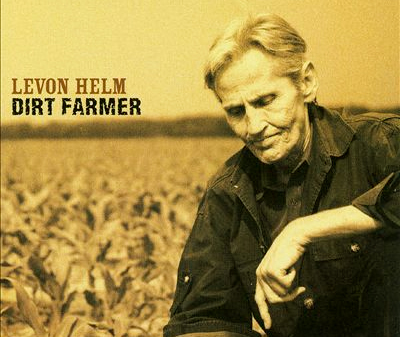

My wife Melissa had gotten us tickets to see Helm and his band at the Orpheum Theatre in Boston when he was touring in support of Dirt Farmer. After having read Steve Jordan’s interview with Helm in Modern Drummer and heard bits of the album on the radio, I’d picked it up and fallen in love with it. I had seen Helm before when my dad took me to see Ringo Starr’s All-Star Band in 1990 in Buffalo. I remember I’d enjoyed seeing Helm and Rick Danko play, but that was overshadowed by seeing a Beatle live for the first time. Helm had played drums and harmonica that night, and that stood out to me, but for some reason, it didn’t make me dive into his music any further at that point.

But that night at the Orpheum, something clicked. Helm had a killer band, including his right-hand man Larry Campbell, his daughter Amy Helm, and a full horn section. And his drums, as always, were stage right facing the band. That meant he could sing and play drums while still facing the crowd, the way a lead singer would, and still be able to lead the band if need be. I hadn’t yet absorbed enough history of the Band to know this is the way he’d been doing it for decades. It was still new enough to be a surprise to me.

It occurred to me that night, watching everything Helm did, that he’d created the perfect show. Every song was a winner. Every musician was as soulful as they were technically proficient. The songs came from everywhere – “Deep Elem Blues” off the new record, a cover of Bruce Springsteen’s “Atlantic City” (in an arrangement I would later find on a later Band album without Robertson), Ray Charles’s swinging “I Wanna Know.” And of course some select tracks from the Band. Phoebe Snow joined them for “I Shall Be Released.” “Long Black Veil” haunted me for days. It was part concert, part barn party, and complete joy from start to finish. And not a single hollering jerk in the crowd. Everyone was rapt, most were singing along.

Later, when I got to see Helm at one of his Rambles at his place in Woodstock I’d see that was precisely the feel he’d been working on his whole career, based on how he had experienced music. He was the son of sharecroppers in Turkey Scratch, Arkansas, a link to another age altogether, and he saw rock and roll as it was being built. At six years old in 1946, his first live show was Bill Monroe and His Blue Grass Boys playing in a tent in nearby Marvell. His family stood in crowds, segregated by the center isle into black and white sections, to watch the traveling medicine and minstrel shows. He saw Elvis in a high school gym, and Sonny Boy Williamson set up shop on a depot loading dock. He distilled all of that in his live shows.

Drums were my first instrument. And when I was a kid, I idolized a lot of great progressive rock drummers. Ringo was there first, but Neil Peart of Rush and Stewart Copeland of The Police were in the mix pretty quickly. I still love that music, too. And I’ll still put my headphones on and play it. Melissa and I had seen the Police reunion at Fenway in the summer of 2007, a few months before Levon’s show. It was a good show to see, and I was happy to finally hear Copeland mix it up live, in person. He was forceful and creative, and the music just as tuneful. But seeing one of my childhood heroes didn’t move me the way Levon’s show did. Levon forced a shift in my thinking, in my disposition toward music, after that Orpheum show. Every ruff and drag and fill was crisp and exactly what the song needed. Throat cancer had taken some of the breadth from his voice, but none of its depth. His playing, and the way he interacted with the band, invited everybody to be a part of the experience. Perhaps most importantly, every note, from dirge to dance number, was filled with joy.

The trickle started after that. I had to hear “Long Black Veil” again, so I turned to Big Pink. I had the bounce in my bones for “Up On Cripple Creek,” so I went to the eponymous second album. And that’s where it really got cooking. “Rag Mama Rag,” “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” “Lookout Cleveland,” “Across the Great Divide” – all of them are classics, even if some get stomped into the ground on classic rock radio and others almost ignored completely. This is how you build a song. You find out what it needs and you cut everything else out.

That was the effect Levon and the Band had in ’68 and ’69. Big Pink helped precipitate Eric Claption’s decision to leave Cream. “This is what it’s all about,” he remembers thinking, in an interview for Bio.com. “And I’m in the wrong place with the wrong people doing the wrong thing.” In the book Across the Great Divide: The Band and America, George Harrison called them “the best band in the history of the universe.” Roger Waters, who was part of a touching tribute at the Love for Levon show, has said Big Pink was a very important record for Pink Floyd.

What everybody else had known for years, it seems, I was just internalizing. There was a lot of turmoil surrounding The Band. The rift between Levon and Robbie Robertson, Richard Manuel’s suicide, Rick Danko’s death. And if you watch the documentary Ain’t In It For My Health, there are moments you can feel every ounce of that on Levon’s brow.

Onstage, that was all gone. When I went up to Woodstock to interview him for The Boston Phoenix in 2011, I wound up sitting on the “radiator seat” about three feet behind him for the entire show. His voice was gone halfway through, but he reached everybody in that room, and made sure he turned around once or twice and gave me a smile. I was the audience, too. And I had found him just when I needed him.

My own musical ambitions are infinitely, regressively humbled in the context of this story, but it is, at its heart, a personal story. So I will allow myself this. I played drums and wrote songs differently after 2007. The album I finally released in 2015 after years of threatened to do it owes a lot to my discovering Levon and The Band. Listen to the first track, “Live Through You,” and it may be more than obvious. I may have written that song some other way without Levon, but now it’s got bounce. And it has, to me, anyway, joy.

After Levon died in 2012, a lot of people wrote about his fantastic second act. The two studio albums, Dirt Farmer and Electric Dirt, and his live album, Ramble at the Ryman, all won Grammys. And he did that all after coming back from throat cancer. I’m grateful for that second act, because I might not have found something important without it. That’s the thing about inspiration – as long as it comes, it’s never too late.

Beautiful tribute to Levon – and a lot more. Thank you Nick.