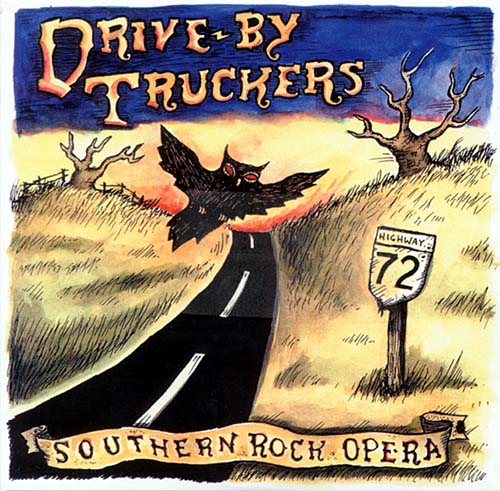

I discovered the Truckers by chance. There was a pile of free CDs in the backroom of the Borders where I worked for a while when I was trying to establish myself as a freelance writer. I was the only one, I think, who ever took from it, and I would eat up everything I could to supplement whatever I was buying in the days before everything was streaming (I still buy CDs whenever possible, rather than download – it feels like an empty experience). My job was to shelve new books and music starting at seven a.m., after our morning meeting, and if I were lucky enough to get the music detail, I could listen to whatever I wanted alone on one side of the store hours before the place would open, enough time to get through the entirety of Southern Rock Opera.

I was barely awake when I heard the opening fuzz and static. I don’t know what I was expecting, but I know it wasn’t a spoken word piece about a couple of kids in a car accident. I didn’t go in completely blind – I had read something about the album somewhere, which is why I picked it up when I saw it in the free pile. The reviews had mentioned a three-guitar attack a la Lynyrd Skynyrd as far as the sound, and a defense of southern rock in the philosophy. That just barely scratched the surface of what Southern Rock Opera offers.

That morning, I was challenged to think about any number of preconceived notions. About politics. About music. About storytelling. They sang about the Neil Young/Lynyrd Skynyrd feud played out in “Southern Man” and “Sweet Home Alabama,” concluding the South could use both of them. It was, as they put it, “the duality of the southern thing.” “Ain’t about no foolish pride, ain’t about no flag/Hate’s the only thing that my truck would want to drag.” The Truckers were proud of the music that came out of Muscle Shoals (I would find out later Patterson Hood’s dad, David, played bass in that scene), pointing out how that racial divide disappeared once you had the rhythm section working. They even took on George Wallace.

It was intellectually satisfying. And also musically thrilling. And I recognized some of the people Hood and and Mike Cooley were singing about. I was a kid who grew up going to the Rochester War Memorial to see rock shows. That meant the world to me when I was a kid, and it might even mean more to me now. Here was a band picking up the banner the bloated arena gods had trampled, mending it carefully, and flying it with all the passion rock and roll was meant to have all the way back to Chuck Berry. And it sounded great pushing the limits of the speakers at Borders.

And it all ended with the plane going down. The fatalistic full-tilt boogie of Cooley’s “Shut Up and Get On the Plane,” a celebration of excess on the road in Hood’s “Greenville to Baton Rouge,” which ends in a hail of guitars that sounds like a plane going down from a seat over the wing. And then “Angels and Fuselage,” time suspended long enough for Hood’s narrator to realize he’s going to die, how quickly he’d moved from life’s endless party to being “scared shitless,” seeing the angels in the trees waiting to receive him.

The Truckers have mostly dropped “Greenville” from that sequence live and frequently play “Shut Up” and “Angels” back-to-back. It’s a one-two punch that never loses its effectiveness (see below starting at 13:44). Especially “Angels.” My heart still seizes up a little bit, and I can see the trees and lakes and roads from that window seat every time I hear Hood sing “I’m scared shitless of what’s coming next.” Inevitable, but he can’t bring himself to say it. A desperate denial I imagine comes with knowing everything is over, you’re just waiting for impact.