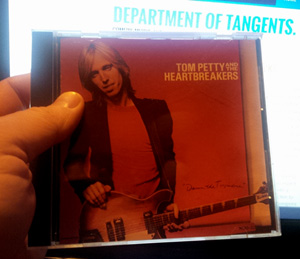

If Tom Petty never recorded another note, never wrote another song, never picked up a guitar or sang again after he released Damn the Torpedoes in 1979, his place as one of rock and roll’s best writers and performers would still be secure. It’s not just that the album is full of hits and radio staples – it kicks off with “Refugee” and includes the classic “Don’t Do Me Like That” and one of the most transcendent love songs in the rock, “Here Comes My Girl.” There’s also no fat on the record. Not a song wasted.

Warren Zanes writes about how this is a tendency in his thoughtful new biography, Petty. Tom Petty’s songwriting has made him rich and famous on a level that’s tough to even fantasize about. “And he’d honored what he’d been given by doing what he could to make the best possible records, one after another,” writes Zane. “He held himself to that. Every song had to count.” That’s evident in the first two Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers albums, the eponymous debut and its follow-up You’re Gonna Get It! But if you were going to try to harvest the DNA that exemplifies that credo, you’d start with Damn the Torpedoes.

Thirty-six years after its release, it remains 36 minutes and 38 seconds of perfection. The album feels… inevitable. Of course this exists. Why wouldn’t it? Nine songs, three of which charted, and another, “Even the Losers,” which eventually joined the others as a staple on classic rock radio. Not that classic rock radio is a great arbiter of quality. But I never switch stations when I hear these songs, and they are still played a lot. I don’t know how many times I’ve heard “Here Comes My Girl” by now. I would have heard it first on WCFM in Rochester, NY as a young teenager, which means it’s been in my life for roughly 30 of my 43 years. And I still feel a glow when I hear Stan Lynch’s drum’s kick in and Petty slide down that A string (I’m assuming it’s Petty – he’d play that static, chugging part while Mike Campbell played the moving figure).

Those narrative verses – the guy sounds truly lost. Nothing makes sense in the world except one thing, and because of that one thing, he can “tell the whole wide world to shove it.” Hey, here comes my girl! Whenever life starts to feel like that, you’re doing something right.

And if you think Petty was just talking his way through the verses and the phrasing doesn’t matter, try singing along. Or pick up a guitar and play it solo. It’s a tough song to get right. Every syllable is placed for maximum impact. Rock and roll is supposed to be played with a certain abandon. And it is on Torpedoes. But if you want to sound good when you let go and play without thinking, you’ve got to put in the work. Petty and the Heartbreakers played some of these songs relentlessly to get them right. In the book companion to the documentary Runnin’ Down A Dream, Petty remembers doing over a hundred takes of “Refugee” alone.

If you can find it, it’s worth watching the Classic Albums documentary featuring Damn the Torpedoes. The whole series was really done, and the Torpedoes episode is second only to the one featuring The Band’s self-titled album. You can hear the isolated 12-string Rickenbacker and the piano on “Here Comes My Girl” and how that made the chorus. And you’ll see what a difference incredibly small details made in drawing the eyebrows on these songs.

Apparently ace studio drummer Jim Keltner hung around the Sound City studio frequently. When Petty and producer Jimmy Iovine were trying to figure out what was missing in the groove for “Refugee,” they grabbed Keltner out of the hallway and gave him a shaker. That was it. That was the difference. Doubt it, but then listen as they pull the fader back and play “Refugee” without the shaker. Still good, but when the fade Keltner back up, the song hits a higher level of groove. “Jim Keltner,” Petty says, “we owe him a lot.”

Then there are all of the songs on the album that weren’t hits, and casual listeners may not have heard. “What Are You Doin’ In My Life” is ferocious, lyrically and musically. It’s puzzling why “Shadow of a Doubt (Complex Kid)” wasn’t a single. “Century City” is a rocker, and takes a not-so-thinly-veiled swipe at the lawyers for his label, MCA, as he was battling to get released from a terrible contract to start Backstreet Records, the label that eventually released Damn the Torpedoes. “You Tell Me” is a slow burner, with the great line, “So you tell me what you want me to do/This might be over honey, it ain’t through.”

Maybe the best of the quintet is “Louisiana Rain.” Petty splits the difference between Dylan and Jagger, singing with poignancy and swagger. It’s some tough poetry. He could release that on an album now and it wouldn’t sound out of place.

There’s always been a satisfying economy to Tom Petty’s music. It didn’t start with Torpedoes and it certainly didn’t end there. He has evolved – listen to Torpedoes, Southern Accents, and Wildflowers back-to-back. But if I ever managed to make something as good as Torpedoes, I might be tempted to quit while I was ahead. And I’m so glad Petty didn’t.